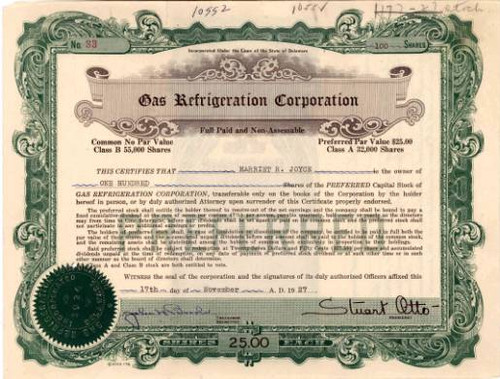

Beautifully engraved certificate from the Gas Refigeration Corporation issued in 1927. This historic document has an ornate border around it. This item has was hand signed by Company's President ( Stuart Otto ) and Secretary and is over 75 years old. All mechanical refrigerators create low temperatures by controlling the vaporization and the condensation of a liquid, called a 'refrigerant'; when liquids vaporize they absorb heat and when they condense they release it, so that a liquid can remove heat from one place (the 'box' in a refrigerator) and transport it to another (in this instance, your kitchen). Virtually every refrigerator on the market in the United States today controls the condensation and the vaporization of its refrigerant by a special electric pump known as a 'compressor.' Compression is not, however, the only technique by which these two processes can be controlled. The simplest of the other techniques is 'absorption.' The gas refrigerator is an absorption refrigerator. Inside its walls, a refrigerant (ammonia, usually) is heated by a gas flame so as to vaporize; the ammonia gas then dissolves (or is absorbed into) a liquid (water, usually), and as it dissolves it simultaneously cools and condenses. The absorption of ammonia in water automatically alters the pressure in the closed system and thus keeps the refrigerant flowing, hence making it possible for heat to be absorbed in one place and released in another, just as it would be if the flow of the refrigerant were regulated by a compressor. The absorption refrigerator, consequently, does not require a motor - the crucial difference between the gas refrigerator and its electric cousin. Indeed, with the exception of either a timing device or a thermal switch (which turns the gas flame on and off so as to regulate the cycles of refrigeration), the gas refrigerator need have no moving parts at all, hence no parts that are likely to break or to make noise. By 1926, when the American Gas Association met in Atlantic City for its annual convention, only three manufacturers of gas refrigerators remained in the field; and of these three, only one - Servel - would succeed in reaching the stage of mass production.24 In the early 1920s, Servel (whose name stood for 'servant electricity') had been funded by a group of electric utility holding companies to manufacture and market compression refrigerators. But in 1925, it had purchased the American rights to the Swedish patents on the continuous absorption refrigerator, and had reorganized (with the injection of five million dollars from the financial interests that controlled the Consolidated Gas Company of New York) to devote itself principally to gas refrigeration. Since it had a manufacturing plant already in existence when it purchased these new patents, it was able to commence production quickly; the Servel gas refrigerator went on the market in 1926 to the accompaniment of a good deal of publicity. The other two manufacturers failed within a few years: they could neither compete with Servel nor sell the machines on which they held patents to any of the large corporations that might have had the resources to compete The trials and tribulations of these small businesses are exemplified in the story of the SORCO refrigerator, which was one of the other two on display in Atlantic City in 1926.26 SORCO was the creation of Stuart Otto , an engineer who had patented an absorption refrigerator in 1923. He owned a factory in Scranton, Pennsylvania, that produced dress forms for seamstresses, and persuaded twenty of the leading businessmen of Scranton to put up five thousand dollars apiece so that he could develop his machine and modify his factory to produce it. These early SORCO refrigerators were advertised in gas-industry periodicals ('Build Up Your Summer Load - and fill your daily valleys: Gas controlled entirely by time-switch to be set by your service man') and were sold to gas utility companies.27 The results of the tests being more or less positive, Otto decided in the fall of 1926 that the time had come to attempt large-scale production: I was not able to raise the money from my stockholders when I informed them that $1,000,000 or more would be required. My only alternative was to buy out my stockholders. So I made an option agreement with them to pay them for their stock within a year. I then went about the country offering manufacturing companies non-exclusive licenses for the manufacture of my machines under our patents, of which some fifteen existed. I licensed Pathe Radio & Phonograph Co., Brooklyn, N.Y., Crocker Chair Company, Sheboygan, Wisconsin, Plymouth Radio & Phonograph Co., Plymouth, Wisconsin. Each of these companies paid me a cash down payment on signing of $25,000 and agreed to a guaranteed minimum of $35,000 per year royalty on a 5% of net sales, for 17 years. Otto had tried to interest General Electric and General Motors in his refrigerator. General Electric was, however, just about to bring out its own refrigerator; and General Motors had just purchased the patent rights on an English machine that utilized a solid rather than a liquid solvent. Otto was trying to enter the national market with ludicrously small sums of money; the days in which David had any reasonable chance of succeeding against Goliath had long since passed. Within a few years, Otto was forced to acknowledge failure: 'Unfortunately . . . we were not financially able to carry the loads. After two years I managed to collect only a small portion of the accrued royalties. Thus, Servel was essentially alone: from 1927 until 1956, (when it ceased production of refrigerators), it was the only major manufacturer of gas-absorption refrigerators in the United States. Never as highly capitalized as its competitors in the field of compression machinery (G.E., after all, had invested eighteen million dollars just in its production facilities in 1927, when Servel's entire assets amounted to not more than twelve million dollars), Servel had entered the market somewhat later than the other manufacturers and was never able to compete effectively. The gas utilities, notoriously conservative companies, were defending themselves against the encroachments of electricity and were not helpful; they complained that Servel was badly managed, that its refrigerators were more expensive than comparable electric machines, and that the lack of another manufacturer meant a lack of models with which to interest prospective customers. Servel did not succeed in bringing out an air-cooled refrigerator until 1933, six or seven years after the electrics had done so; and by then the race was virtually lost. For all its virtues as a machine, the Servel, even in its peak years, never commanded more than 8 percent to 10 percent of the total market for mechanical refrigerators. The demise of the gas refrigerator was not the result of inherent deficiencies in the machine itself. The machine was not perfect when it was first brought on the market, but it was no less perfect than the compression machine, its rival. The latter succeeded for reasons that were as much social and economic as technical; its development was encouraged by a few companies that could draw upon vast technical and financial resources. With the exception of Servel, none of the absorption manufacturers was ever able to finance the same level of development or promotion; and Servel never approached the capabilities of General Motors, General Electric, or Westinghouse. The compression refrigerator manufacturers came on the market earlier and innovated earlier, making it doubly difficult for competing devices to succeed. The fact that the electric utilities were in a period of growth and great profitability between 1920 and 1950, while the gas manufacturers and utility companies were defensive, conservative, and financially weak, cannot have helped matters either. If Stuart Otto had been able to obtain either capital or encouragement from the gas utilities, if Servel had been managed well enough to have innovated earlier, if either one of them had been able to command a chemical laboratory capable of discovering a new refrigerant, if there had been a sufficient number of gas-refrigerator manufacturers to have staged price wars, or license innovations to each other, or develop cooperative promotional schemes along with the gas-utility companies - well then, the vast majority of Americans might have absolutely silent and virtually indefatigable refrigerators in their kitchens. The machine that was 'best' from the point of view of the producer was not necessarily 'best' from the point of view of the consumer. The above history was obtained from the from The Social Shaping of Technology: How the Refrigerator Got its Hum, Donald MacKenzie, Judy Wajcman, eds. Open University Press, 1985 by Ruth Schwartz Cowan.

Gas Refrigeration Corporation 1927 signed by Stuart Otto

MSRP:

$295.00

$195.00

(You save

$100.00

)

- SKU:

- gasrefcor

- Gift wrapping:

- Options available